The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Homecoming Court

Schools across the US have begun to forget the original intention of Homecoming Court.

The 2022 Homecoming Queen and King, Lailah Downs and Tyler Small, standing next to the mighty Griffin

October 24, 2022

LOS ALAMITOS, CA — Los Alamitos High School’s student body expressed discomfort and criticism regarding the stigma behind Homecoming Court.

The initial purpose of the Homecoming Queen and King, a tradition that dates back to the early 1900s in the South, was to honor graduates who were returning to their alma mater. Additionally, as a school fundraiser, with money raised going toward scholarships and other campus enhancements. Similarly, Los Al takes pleasure in consistently upgrading the school grounds, student life, and educational opportunities. However, year after year, more and more of the student body begin to forget the initial intent of the Homecoming dance. With the popularization of Homecoming Court arising in 1925, schools each year have begun to shift their focus from charity to popularity. Los Al is guilty of this.

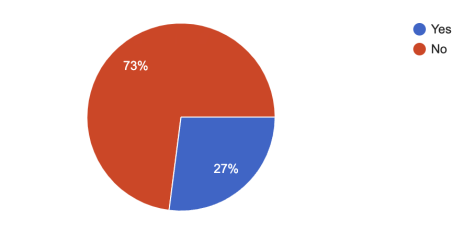

In a recent Google Form survey conducted over a three-week period, 73% of participants responded with not like the current method of how the Homecoming Court is promoted. With that being said, the majority of voters enjoy the idea of a Homecoming Court at our school.

“I always want to support someone that’s passionate about the school,” one participant in the survey said. Homecoming and other large school events allow the student body to come together and participate in the name of school spirit. However, in regard to nominating who will be presented on the Homecoming Court, students and nominees alike discussed the discomfort of the nominating process itself.

“I wasn’t comfortable voting for someone based on their popularity with the majority of people. I honestly didn’t know any of the nominees that I could relate to or had any similar interests,” another voter said. Although it’s impossible for every student on campus to be aware of all nominees, it shows the lack of awareness a majority of the student body experience when deciding who to nominate and vote for during Homecoming week.

“I pretty much just vote for whoever I see posted about the most,” a participant said. Days leading up to voting, hundreds of social media accounts flooded with posts promoting a student’s nomination for court. Although mass promotion is an excellent strategy for a message to reach more audiences, in excess, students find them to be “annoying” or “repetitive.”

“Honestly, it gets annoying. I hate seeing the same five people on the Instagram feed for a week straight,” one participant said. Having a Homecoming Court is nothing to be ashamed to be a part of, infact, it’s a great honor to be nominated. Ava Widener, a senior on the Homecoming Court, describes the entire event as an incredible experience: including nomination promotions.

“I think think this year was really good with promotions… not too much,” Widener said.

In contrast to previous years, Los Al changed its emphasis from a material perspective to more of a recognition of the school’s prior accomplishments; the game’s halftime show on Friday honored John Barnes, a renowned football coach, and mentor. Those standing next to him were former Los Al football players from the same year they defeated Mater Dei in the CIF title game.

This demonstrates how Los Al has started to change its emphasis from a Homecoming that prioritizes popularity to one that strikes a balance between entertainment and the commemoration of both recent and historical scholastic accomplishments. The Homecoming Court is not the problem; it fosters student cooperation. However, it’s crucial to recognize not only the Homecoming Queen and King but also the significance of the occasion as a whole.

Isabella Gasper • Oct 27, 2022 at 1:38 pm

This article is amazing. I love how you added both sides because it made me think deeper about Homecoming. Great job!