LOS ALAMITOS, Calif. — Known for its rigorous classes and competitive nature, Los Alamitos High School offers many Advanced Placement classes across a range of subjects, but specifically shines in its science, technology, engineering and mathematics classes, undoubtedly considered some of the hardest classes on campus and the hardest AP classes.

However, while teachers are more than qualified to teach these courses– calculus, physics, computer science, biology, chemistry, environmental science, and more– there is a frightening number of students dependent not on their class notes and teacher-provided resources, but on AP preparation materials created and sold by outside entities, tutoring, College Board (the college preparatory entity that owns and administers the SAT, AP and their respective classes materials) and on each other. Why is this? Why is it that accredited individuals can’t seem to pass on the knowledge that we know they have to eager and determined students?

From this undeniable shortfall, a dependency on self-teaching by students has arisen. Because teachers know that students are driven to succeed, the necessity, or perhaps even motivation, to teach is not present; if students will find a way to learn the material they will be tested on, both as a part of the course and part of the national exam, good teaching seems like a nonessential component. It is also important to note that AP classes vary based on the school, primarily due to the teacher’s interpretation of the course.

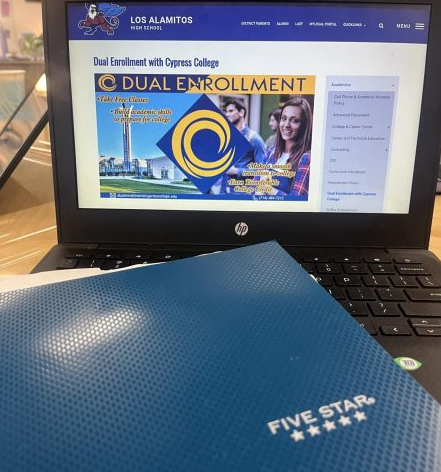

“The AP Program does not supply syllabi for AP courses. We supply a detailed set of expectations about what content a college-level course in that subject should cover. AP teachers design their own syllabi with these standards in mind,” said AP Central, the College Board conglomerate for all things AP-related.

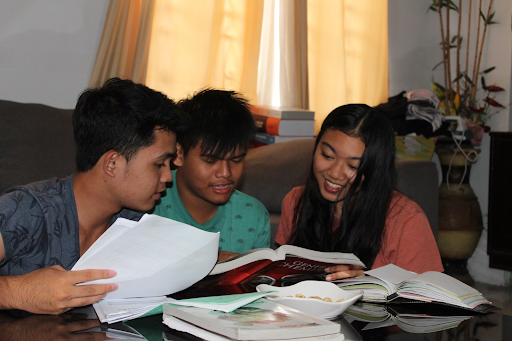

The frustration here lies in the falsehood of registering and enrolling in a class promised to provide hands-on experience and quality education in a highly decorated school, but also in the variety of learning styles- and “teaching” styles- that are disproportionately neglected. Many students struggle severely to learn from reading a textbook or watching a video; we learn best when taught face-to-face, through asking questions and by doing, forcing us to turn to our friends. This burden is mutual and has created an unshakable bond amongst many students in this sphere of classes; however, it has also spurred on the competition, pettiness, and secrecy among those with greater access to learning resources outside of the classroom, grades and Grade Point Averages, and who is “smart” versus who is not.

Moreover, the convoluted nature of AP classes creates further obstacles for students as first-time and last-time enrollees in these courses; this struggle is further heightened for students new to AP courses as a whole. The professionals trained in the course content, testing, test composition, and ever-evolving complexities of the test are necessary; these teachers are–or, rather, should be– a wealth of knowledge, their years worth of teaching this specific course meant to serve us best, especially considering that no one person could possibly learn the in’s and out’s of a course, most of these courses having existed for 70 years, in a single school year. Years’ worth of compounded knowledge could be the difference between a student receiving college credit (which is the entire purpose of taking an AP course and AP test) and not.

“I have self taught pretty frequently, especially with AP bio and AP physics. I definitely rely on a lot of outside resources,” said LAHS senior Jessica Peng.

College Board boasts the benefits of enrolling in AP courses, but more often than not, students leave them feeling dejected, unsatisfied, and disappointed with their inability to succeed, despite the systemic barriers that are preventing them from obtaining the type of education promised, in turn damaging their mental health and overall well-being.

“AP students … dig deeper into subjects that interest them and learn to tap their creativity and their problem-solving skills to address course challenges,” says AP Central.

While this struggle exists to a degree in all AP courses, and possibly even all departments on campus, nowhere is it as profound and acute as in the STEM courses. Perhaps this unique set of expectations and culture within this world is linked to culture within the STEM world outside of high school and academia in general: the systemic barriers against women, people of color, and limits on diversity in general; the lack of accessibility, educational disparities, and hostility often felt; the unwavering confience and determination necessary to survive in a lab as a undergraduate, graduate, or post graduate researcher; the high stakes and stress of med school; the institutional control and limits on funding. The list goes on. And on. And on.

After previously garnering awards in national excellence as a National Blue Ribbon School, California Distinguished School, California Gold Ribbon School, Golden Bell Award, and California Business for Education Excellence Award, the self-teaching epidemic directly opposes everything the Los Alamitos Unified School District boasts in Academics–one of the Four A’s (“Academics, Arts, Athletics, and Activities”)– pillars that define our campus and district philosophy. We preach student and faculty connectedness, offer extensive opportunities to our students, and ultimately intend to set them up for success, whatever that may mean for them. If we wish to continue to uphold these values, we must find a remedy for this contagion– now.