Behind the front line: L.A.’s hidden environmental heroes

LOS ANGELES, Calif. — Pandemic and natural disasters have struck this generation one after another, but people look on from behind their screens, seemingly unable to help.

Brittany Spiller, Liesl McConchie, Dr. Richard Corsi and Siobhan have a different mindset.

Brittany Spiller has lived in Rossmoor since 2019, but her husband’s family has roots in the area dating back to the 1960s. When Spiller’s son was diagnosed with a heart defect shortly after birth, the world was suddenly a much scarier place.

Researching air purifiers, masks and air quality became part of her daily life. When air purifier filters began to darken with particle matter quicker, and a nebulizer was being used in the house frequently, Spiller realized the severity of Rossmoor’s air quality issue.

“I don’t know why it didn’t click until then, but we live in the armpit of two freeways. We got the 605 on one side and the 405 on the other. It makes sense that the air has a little bit more particle matter in it here,” Spiller said.

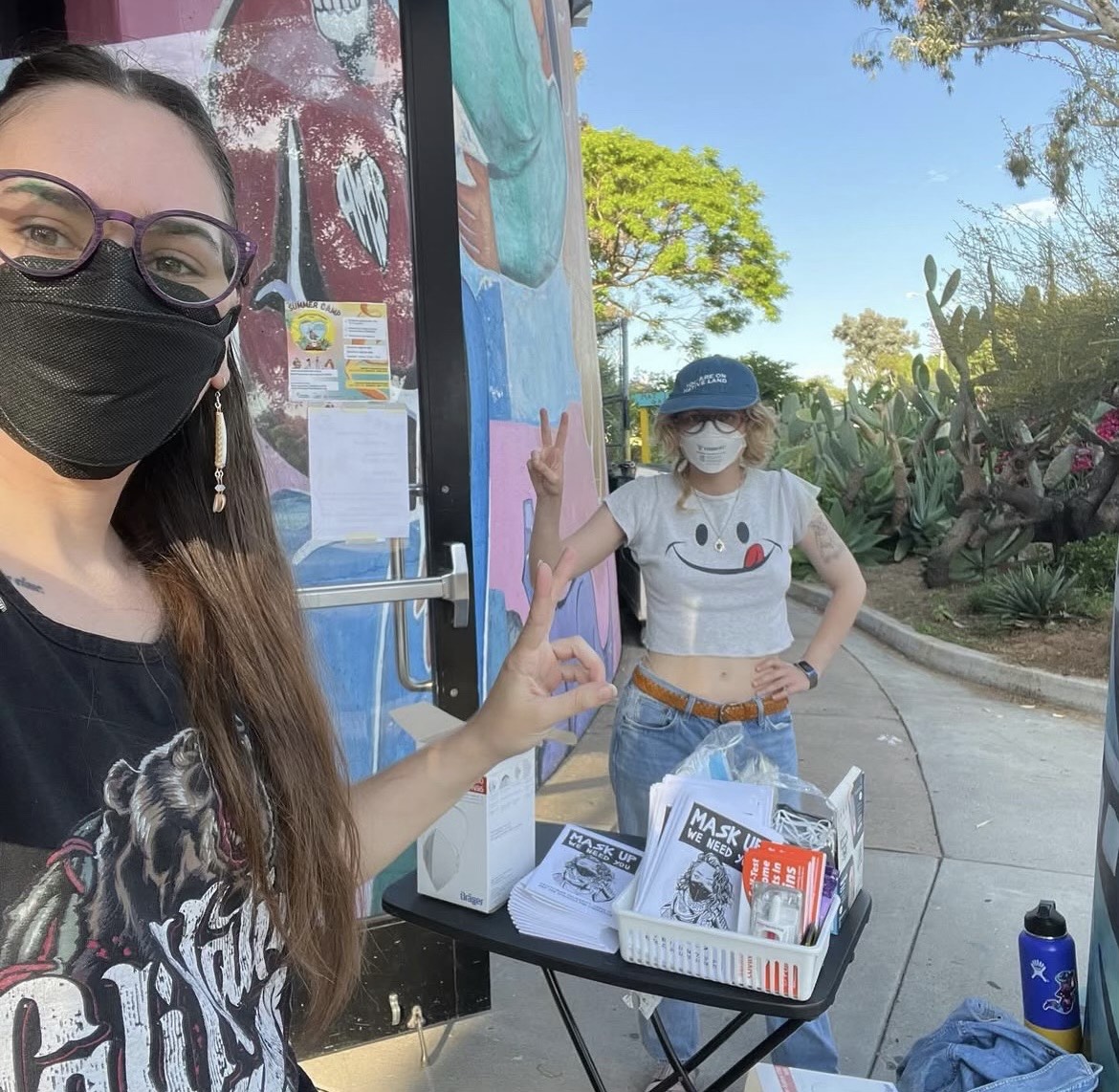

She soon discovered Mask Bloc, an organization that aims to make accessible equipment that keeps people safe from the dangers of air quality. Spiller learned that donating masks is the simplest way to help those affected by poor air quality.

She actively looks for opportunities to acquire masks at affordable prices, such as government auctions or companies liquidating their Covid-19 masks. Recently, Spiller acquired a pallet of hospital masks that she found posted as a “curb alert.” Afterward, she contacted a local mask bloc to see if she could donate them.

Though she does not personally hand out the masks, she coordinates with organizers to distribute them to the public. So far, she has donated close to 20,000 masks to the Los Angeles Mask Bloc.

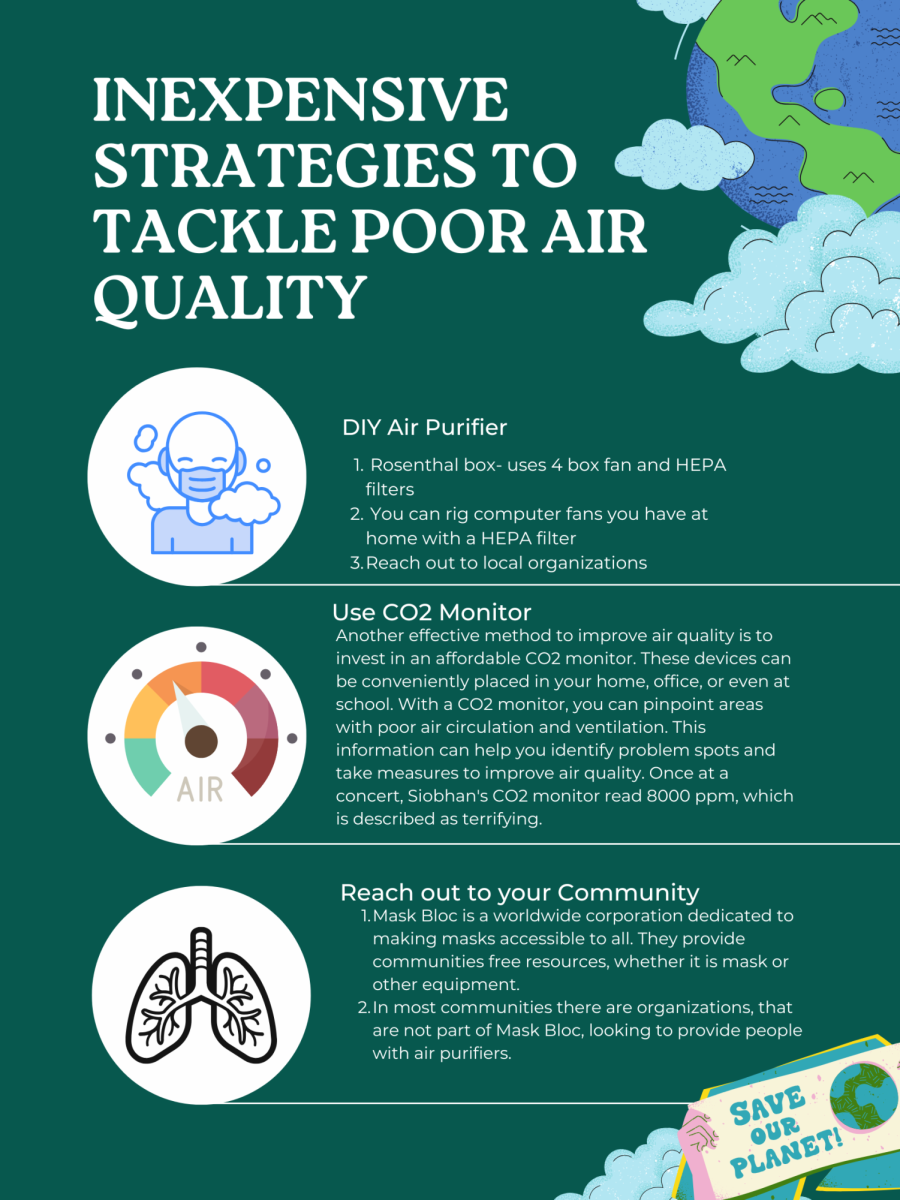

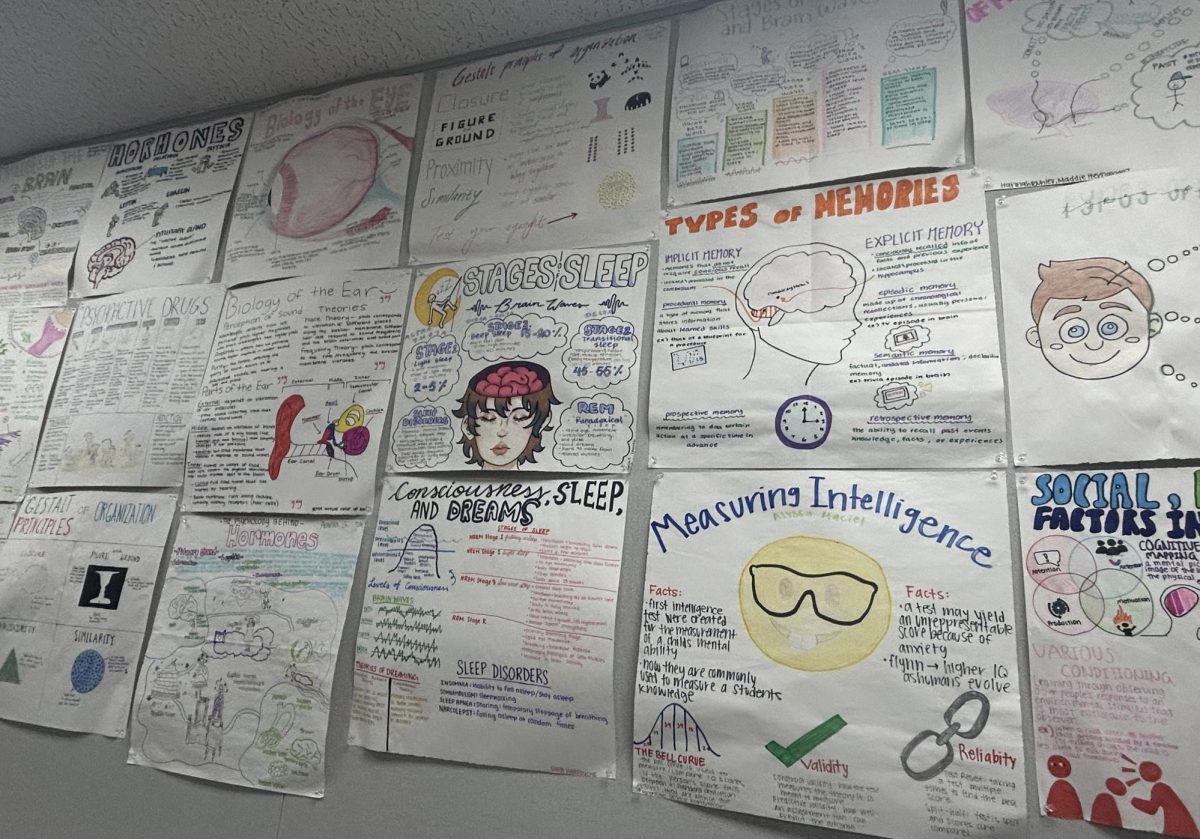

On top of donating thousands of masks to organizations, Spiller focuses on improving air quality within classrooms. A study from Harvard found that indoor CO2 levels rising by even 400ppm would reduce cognitive functioning by 21%.

“Everybody wants their kids to succeed and do well in school,” Spiller said. “I feel like we owe it to our children to give them every tool and accommodation possible, and something as simple as increasing ventilation in the classroom can impact success.”

Spiller shared one of her recent experiences driving masks up to L.A. school districts for children to use.

“It was really funny trying to drive (mask pallets) up from San Diego because we managed to fit 16,000 masks in the car,” she said. “You should have seen the man in the car next to us when we were in the parking lot! He was laughing while we were packing masks into the car.”

Some nearby Mask Blocs are located in Long Beach (@maskbloclongbeach on Instagram), Orange County (@ocmaskbloc on Instagram), L.A. (@maskblocla on Instagram) and San Diego.

Recently, San Diego Mask Bloc worked in Mission Valley to put together Corsi-Rosenthal boxes and drove them up to L.A. and Pasadena to hand out. Various organizations, though in separate locations, work together, especially during emergencies.

Liesl McConchie’s story started in the classroom. Her combined love of learning and dream of becoming a high school math teacher propelled her through college.

When she realized students were, unfortunately, not as enthusiastic about math as she was, McConchie took it upon herself to learn about the brain, specifically a student’s brain, to better herself as a teacher.

20 years later, she pooled her findings into her first book, published in early 2020 with Eric Jensen: “Brain Based Learning.” In the book, McConchie discusses how air quality impacts cognition, creativity, health and test scores — all very important to her.

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, people around McConchie joked about chugging hot sauce and withstanding the smell of dirty diapers. But as someone who studies the brain, McConchie realized the virus was breaking through the blood-brain barrier and attacking the brain’s senses, something much more serious.

“As a mom of three young kids who go to school, I was like ‘I really need to figure out how I protect my family and my kids from this virus,'” McConchie said. “That’s when I learned that the virus is airborne and can stay in the air for hours, depending on the air quality in a space.”

She became involved in understanding the airborne nature of the virus, collaborating with experts like Dr. Richard Corsi, Dr. Kimberly Prather and Jim Rosenthal.

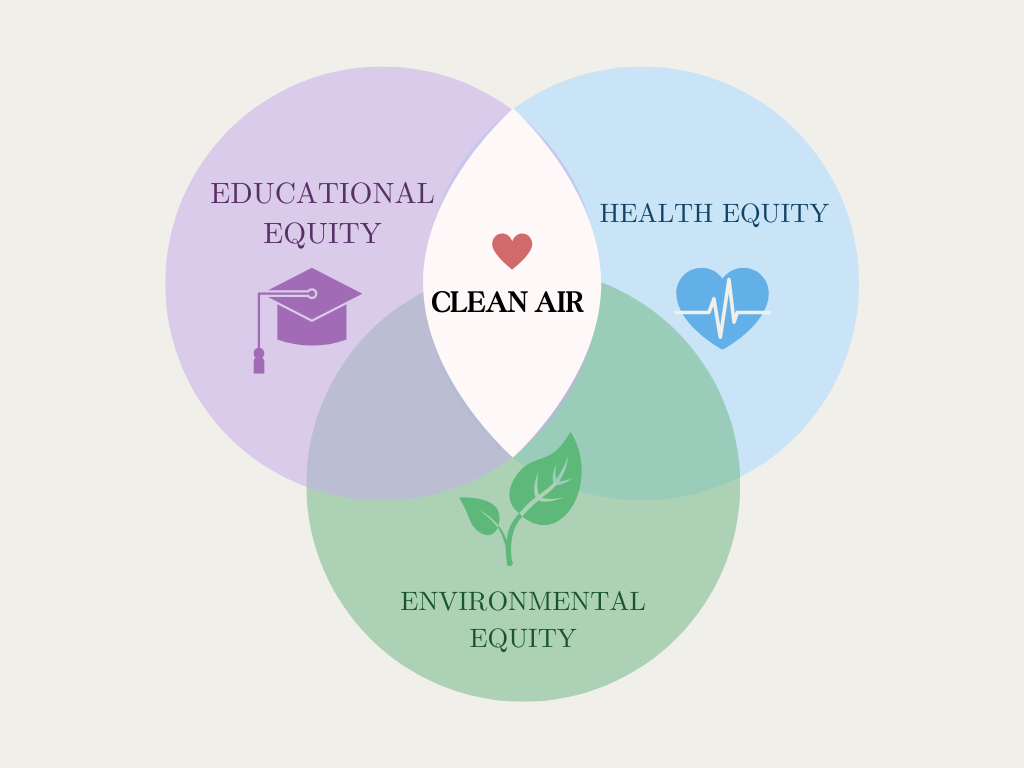

McConchie’s mission is driven by equity and distributing resources to all, no matter their socioeconomic status. She believes that the most privileged and wealthy people should not be the only ones receiving protection from bad air quality.

To McConchie, just because you can’t see air quality does not mean it is not a huge factor of our health, hearts and brains.

“Think of a Marvel movie. They have the big, scary villain, but it’s the stealthy, invisible villain that can really do damage. That’s air quality. I want future generations to know that the air we breathe matters, and everyone should have access to clean air,” she said.

McConchie believes that clean air is just as important in schools as clean water: breathing good-quality, clean air deserves as much care as filling up a water bottle with filtered water on campus. That’s why she co-founded the California Alliance for Clean Air in Schools and Corsi Rosenthal Foundation, where she and her colleagues work to change policies to make clean air universal.

Currently, McConchie is bringing air quality awareness to classrooms.

“I would love for this to be part of a science or math lesson, for students to be learning about this and then doing a STEM project of building a Corsi-Rosenthal box and checking the monitor and watching the invisible particles drop on the screen. It’s so empowering,” McConchie said.

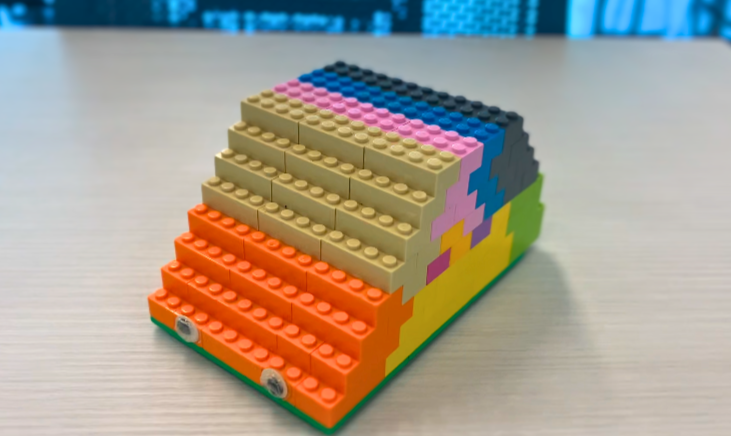

One of McConchie’s teaching tools is this model of a brain constructed out of LEGOs. Its colorful sections represent the limbic system: hypothalamus, hippocampus and amygdala.

In the future, McConchie plans on continuing to share her knowledge and advocate for change in classrooms.

Richard Corsi grew up in L.A. when air quality remained a foreign concept to most people. He knew he wanted to follow a path focused on improving air quality.

He attended Humboldt State University (Cal Poly Humboldt) for the courses it offered in environmental resources engineering, allowing him to delve into the world of air pollution.

After researching outdoor air quality, he realized that indoor air quality was another problem to tackle. He recognized that most Americans breathe air pollution indoors — places like home, office and school spaces.

Over the years, Corsi’s focus moved to areas that did not receive the same attention and resources to reduce exposure to indoor air pollution. Small housing units with many occupants allowed infection rate to spread rapidly, affecting residents’ mental and physical tasks. Others couldn’t afford air cleaners or respirators. Corsi kept these families in mind while developing the Corsi-Rosenthal box during the height of the pandemic.

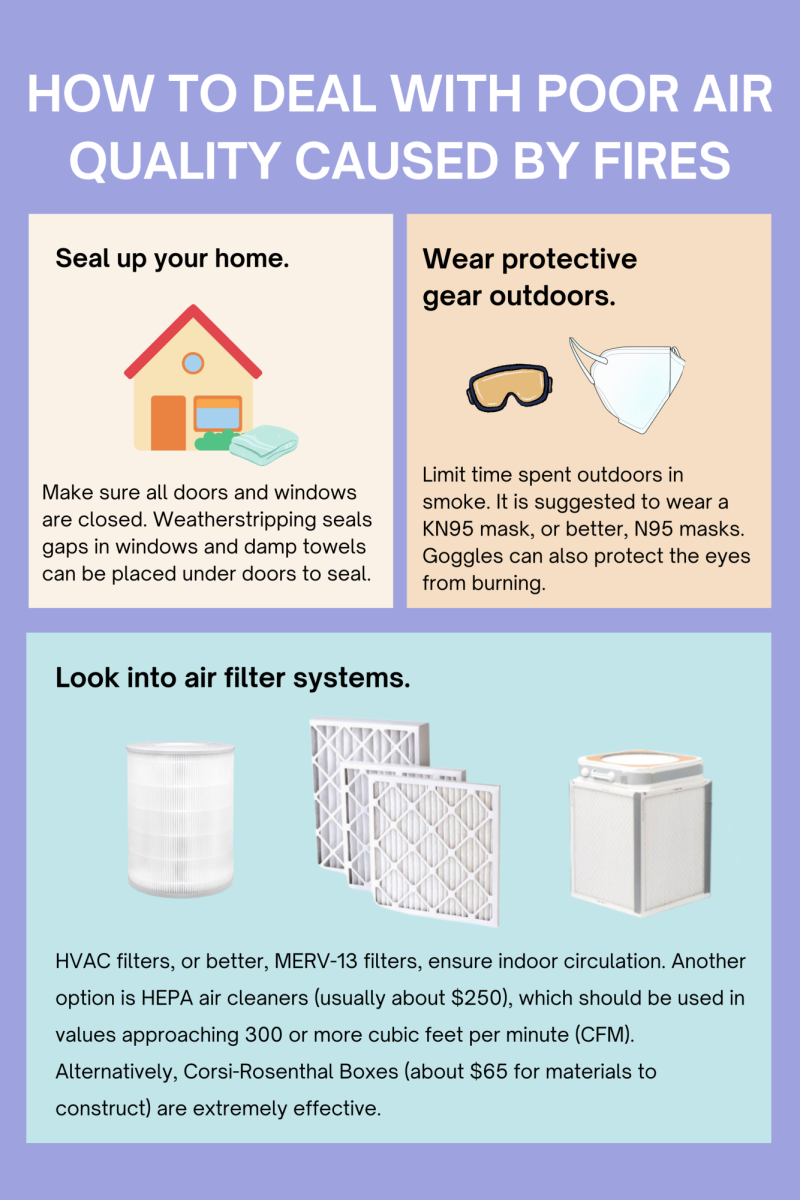

One way to construct the system includes four MERV-13 filters, cardboard and a box fan sealed with duct tape. This effectively reduces air particles carrying airborne viruses and dust from wildfire smoke. Read how to make your own Corsi-Rosenthal box here.

Corsi encourages families battling indoor air pollution caused by wildfires to seal doors and windows, wear protective equipment and invest in air filtration systems.

To Corsi, the next student signing up for a lecture on air pollution could be the next engineer to develop a life-changing air filtration machine.

Siobhan lives in San Diego and is part of the San Diego Mask Bloc. Having witnessed the devastating impacts of COVID-19 and the lasting toll of HIV/AIDS on her family, she is driven by a desire to prevent unnecessary suffering and protect vulnerable populations.

Her journey began with a realization that behind the walls of COVID-19 is a hidden, harmful problem: poor air quality. She recognized that the leading source of microplastics comes from synthetic fibers in our clothes and other materials. Inhaling these particles significantly impacts our health.

Her uncle’s death from HIV/AIDS deeply shaped her views, as her family saw firsthand how a novel virus can cause suffering and death. The pain of watching a loved one suffer led her to take action, and she was determined to prevent others from enduring the same fate.

“My motivation is to prevent death, protect culture and language, protect land protectors and vulnerable people — everyone, really — but mostly the vulnerable populations who are most affected,” Siobhan said.

As an indigenous person from Orange County, she understands environmental racism and health. Marginalized communities, whether due to race, class or geographic area, often face the harshest exposure to dangers like bad air quality. From sewage exposure in South Bay to pollution in urban cities, these communities are constantly at risk.

Siobhan believes that clean air is a human right. The world has made progress on improving water quality but overlooks the dangers of poor air quality. When progress is not made, it is clear that we are not seeing an equitable distribution of clean air.

“I feel like clean air is the next frontier of climate crisis that we’re not prepared for and not paying enough attention,” Siobhan said.

Siobhan is focused on empowering people to better understand media literacy and identify disinformation. Most people and communities do not have the time to sit through trainings and read many articles, so she wants to spread awareness and encourages others to do the same.

“The most rewarding part has been breaking out of those echo chambers and making sure this information gets to the people who are most harmed by all these factors,” Siobhan said.

High quality air purifiers are beyond the budget of the average American family. On average, a nice air purifier costs anywhere from $100 to $1,000. Siobhan believes everyone should have access to air purification no matter their geographic location or wealth. There are many effective air purifier solutions.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Los Alamitos High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Scarlet Davis • Mar 3, 2025 at 8:42 pm

You both did really good! I like how both of you were able to write about the environment and inform people what to do if there was a fire again! Great work

Alyssa Mathews • Mar 3, 2025 at 7:40 pm

All of these people are so inspiring! You both did a great job highlighting what they do!

Art Remnet • Mar 2, 2025 at 5:52 pm

Very well done article. Great storytelling and research.

Thanks for sharing!