California drought: How to make sense of the climate

Recent rains have mitigated the effects of the severe drought California has experienced for the past few years.

Flora and fauna in California enjoyed the recent rainy season.

February 10, 2023

LOS ALAMITOS, CA — Californians have been told constantly for the past few years that the state is in a severe drought. With the heat waves of last fall and the abundance of rain at the beginning of January, it’s difficult for the average Californian to make sense of the state’s current climate.

Griffin Gazette is taking a deep dive into the multiple layers of complexity that plagues this statewide problem.

What is a drought?

Often, people attribute the word “drought” to low amounts of rainfall. So when we get an exceptionally heavy rain season, it may be difficult to believe that we’re still in a drought.

Mrs. Helm, the AP Environmental Science teacher at Los Alamitos High School, said, “When we talk about a drought, we usually talk about long term climate conditions in which we have significantly less than normal amount of rainfall.”

“Our climate is essentially an average,” continued Mrs. Helm. “We expect to have rain from October to March and there are expected levels of rainfall in a normal year.”

However, the expectations of rainfall can change depending on a variety of factors, specifically during La Niña versus El Niño.

In addition to rainfall, we need to see that our water reserves are running low. We pull from underground aquifers, we pull from snow packs, we pull from rivers and lakes, so we can measure the water levels. — Mrs. Helm

“A single dry year isn’t a drought,” Mrs. Helm said, “because of the state’s extensive system of water infrastructure and groundwater resources buffer impacts.”

Dry weather conditions in conjunction with exceptionally low water levels in California reserves are what qualifies as a drought.

How severe is the California drought?

For every region, climate is impacted by proximity to the ocean. Since a large part of California is on the coast, the ocean temperatures are a major indicator of climate.

Every year for the west coast, there can be two possibilities of ocean temperatures: above average, which is denoted by El Niño, and below average which is denoted by La Niña.

“We have been in La Niña for three years,” Mrs. Helm said. “When the surface temperature of the ocean is cooler than normal, there is less evaporation, which means that there is less precipitation.”

So, overall, winter conditions are generally dryer, which does not help with the drought.

However, despite California being in La Niña, the winter season proved to be overwhelmingly positive in terms of replenishing the water supply.

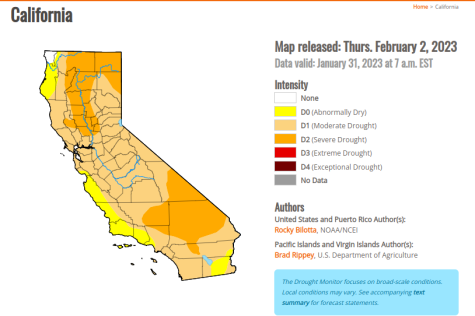

As the key indicates, California drought intensity is not uniform throughout the state. However, most of California falls under the category of moderate drought.

Some regions in the north and desert areas are currently experiencing severe drought; regions toward the coast are in abnormally dry conditions, but are not classified as a drought anymore.

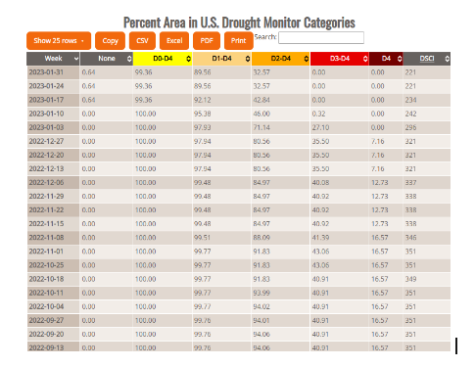

Going back to late September of last year, roughly 16.57% of counties were in exceptional drought, the highest severity.

That figure has steadily gone down as winter progresses. Between Jan. 3 and Jan. 10, massive amounts of rainfall pushed out of exceptionally and extreme drought conditions. Such results mean that the most recent winter precipitation was successful in lifting California out of a severe drought and towards a moderate one.

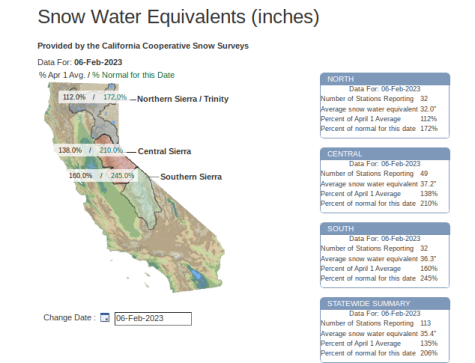

Another crucial measurement for the success of the winter season, in regards to water supply, is the level of snowpack.

“Snow that has fallen on the ground and does not melt for months due to below-freezing temperatures is called snowpack,” says the National Geographic network.

Fortunately, the snowpack this year has been the highest in recorded history, which is a huge victory for California’s water supply.

“The reason snowpack is important is that’s where our freshwater will eventually melt out of,” said Mrs. Helm. The snowpack will replenish California’s reservoirs, lakes, aquifers, and other sources of freshwater.

Snowpack is tracked by the percentage of average snow levels on a given date. According to a graph from the California Department of Water Resources, the snowpack of the Northern Sierra is between 112%-172% of the average on February 6th, 138%-210% for the Central Sierras, and 160%-245% for the Southern Sierras.

While these figures are reassuring of the declining intensity of the drought, Mrs. Helm warns to not misinterpret the data. “It’s not a long-term fix for our climate,” she said. “It’s a good sign for this year. For this year, we should have a good supply of water. But it does not fix how much water we used,” Mrs. Helm added.

What does this mean for California?

For the past few years, Californians have heard constant urges from the state government to cut back on water use.

“Starting June 1, 2022, landscape watering is allowed on Tuesdays and Saturdays only,” said the Long Beach Water Department on their website.

Advocating for water conservation seems to have somewhat worked for California residents.

“Preliminary numbers that reflect 95% of the population show that Californians cut back on water use by 7.5% overall in June this year compared to June 2020,” said CA.gov.

However, citizens cutting back on water use may only be a palliative solution. “Statewide, average water use is roughly 50% environmental, 40% agricultural, and 10% urban,” said the PPIC Water Policy Center.

Therefore, only cutting back on residential water use will not save a majority of California’s water. The solution may rely on the agricultural industry.

Mrs. Helm said, “If we want to reduce [California’s] water use, it’s not the homeowners that can have the impact. We have to regulate businesses; we have to impose on farms.”

Conclusion

Winter is coming to a close; it’s important for Californians to be aware of the current climate crisis. The drought still brings less than ideal conditions for many parts of California. Spreading local awareness is key to finding a solution. Although the threat of low water supplies looms over many Californians, a deep dive into the situation with a cautionary lens is what the state government needs to do. Californians can unite together and do their part to build a sustainable and hopeful future.